Sicily & Tunisia—Late July 1943

Major General Matthew Ridgway, cerebral commander of the 82nd Airborne Division, had a problem.

The recent operation in Sicily had shown that his paratroopers were more than up to the task, proficient in fighting skill; everything else that went with bringing that fighting skill to bear on the Germans was a challenge, however.

In the effort to make as much of the division as air-mobile as possible, they had left their services of supply without the trucks needed to transport the necessary commodities of war in the right volumes, their medical personnel inadequately equipped to deal with the realities of mobile warfare, and two of their four artillery battalions reliant on manpower to move their 75 pack howitzers.

An airborne division should be evolved with a stinginess in overhead and in transport which had absolutely no counterpart thus far in our military organization.

— Lt. Gen. Leslie McNair, Commanding General, Army Ground Forces

They lacked the necessary planes to get the division landed with its support troops, and once they did get to Sicily, they proved to have equipment not commiserate with the job they would be faced with. Lieutenant General George S. Patton, commander of the Provisional Corps under whom the 82nd fell, had to attach part of a medical battalion and a quartermaster truck company to help the division complete basic tasks.

For the 82nd Airborne Division’s quartermaster company, the effort to make them airmobile meant they had 30 classic Willy’s Jeeps - 1/4-ton trucks in Army legalize - to sustain the fight. Even the light combat given during the ground campaign on Sicily had shown “the air landing by glider or plane of thirty (30) 1/4-ton trucks and trailers would leave this division without adequate means to supply itself for sustained action,” in the opinion of Lt. Col. Robert Weinecke, Division G-4. Supply duties were difficult enough, but evacuation of damaged equipment was impossible with the current structure.

In sum, the across the division, it was able to muster only 57 Jeeps and 48 two-and-a-half ton trucks for use to do everything from ferrying troops to supply duties. Captured vehicles were used to the upmost. Major Ivan Roggen, regimental surgeon of the 504th Parachute Regiment, utilized a captured enemy half-track to do his casualty evacuation in lieu of any other vehicles.

The only solution was to motorize. Weinecke knew it, and Major General Ridgway knew it too. On July 29, he made his case. First, to LTG Patton. While Ridgway detailed the deficiencies and needs, he had Ralph Eaton, his erstwhile chief of staff, take Weinecke’s suggestions and lay out the technical details of what equipment - trucks - would be needed to make it happen.

If you are interested in learning more about logistics in the 82nd Airborne, go check out Parapacks Over Holland.

Enter, the Seaborne Echelon

Motorizing meant that not everything the division needed could be brought in by glider or parachute; it was too bulky and too heavy. Thus, an echelon rising from the sea was born.

Shipping then became critical to the 82nd Airborne Division for the rest of the war. It became a major planning factor, bordering on a determinative factor, just weeks later during the flurry of planning for Operations GIANT and GIANT I in August 1943. The 82nd was no stranger to the influence of shipping, however; it had determined the make-up of their division. Originally, they were supposed to be two glider regiments and one parachute regiment, but because there was not enough shipping they could only find the cargo space to take one regiment’s worth of gliders overseas.1

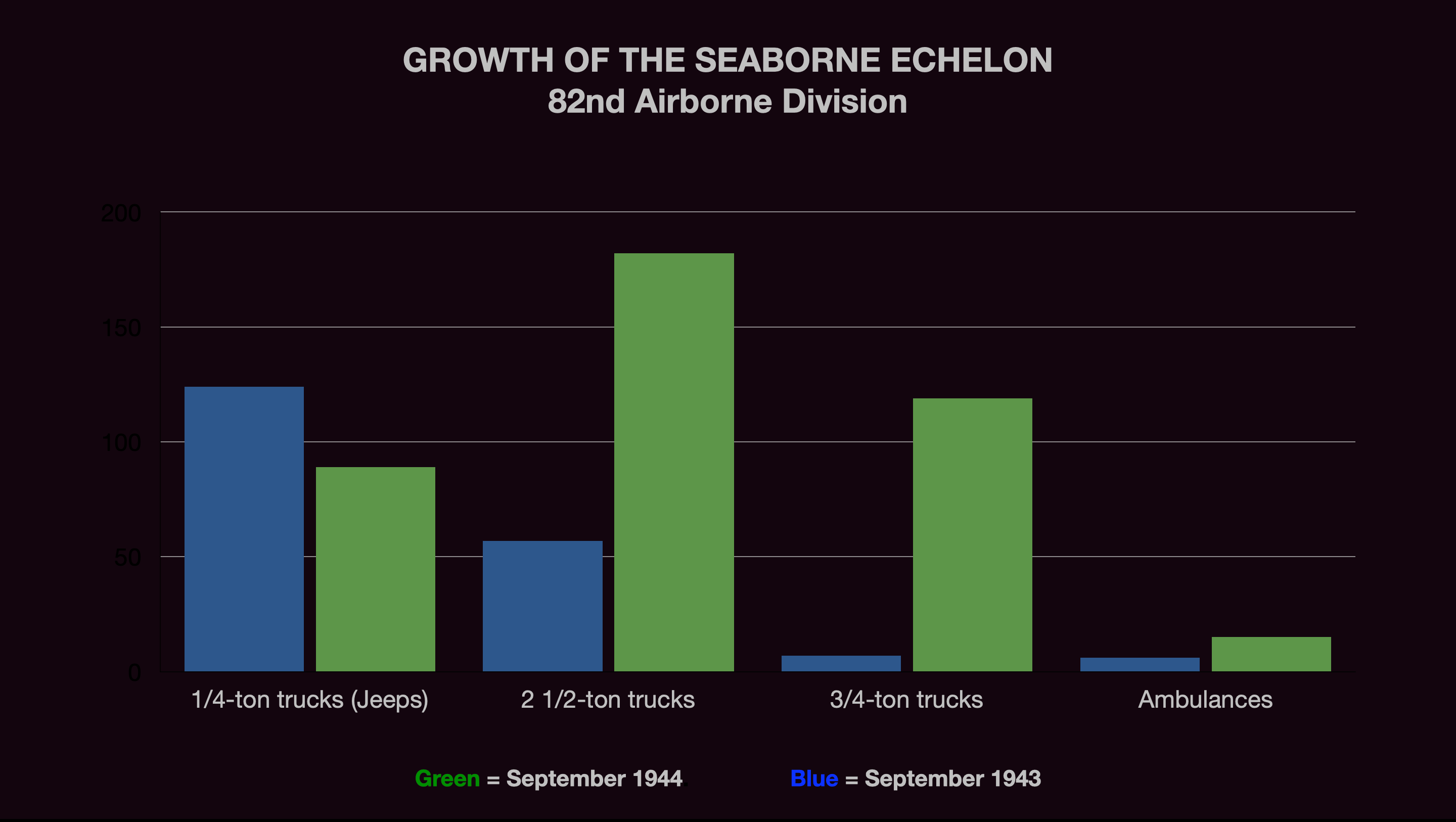

However, increasing the number of trucks made them further reliant on shipping in an operational sense. The following graph shows the growth of the division seaborne echelon in the year between September 1943 and September 1944.

Shipping

The 82nd Airborne Division could theoretically jump and fight anywhere. But only for a period of 3-7 days. Sustained action really required these trucks coming in by sea. Assuming all the division’s vehicles were loaded on Landing Ships, Tank provided by the Navy, it would require anywhere from 13-15 LSTs to support the 82nd Airborne Division. Although Operation Market Garden looked on the surface to be solely an air-ground campaign, it was only possible because of Navy amphibious ships providing critical logistics connectors in support. It’s truly illustrative of the dominantly expeditionary and amphibious nature of the American way of war in World War II.

Photo: The Seaborne Echelon of the 82nd Airborne Division marshaling prior to Operation Market Garden

Next week’s post: Part 1 of The Blitzkrieg Defense: The Battle of Mook

(For the truly nerdy, I broke down by the hard, cold numbers the quantity of trucks in the 504th PIR & the 307th Airborne Medical Company as an illustrative breakdown before aggregating the entire division)

Huston, James. Airborne Team. Historical Division, Special Staff, n.d. P. 160.

This is an excellent read, and it goes great alongside “Parapacks over Holland.” Necessary insight for sustainment leaders today!

This is an excellent example of how to look at a familiar picture and see something startlingly new.