Precision and Dispersion

Welcome to Ridgway’s Notebook, your home for airborne PME. We offer penetrating essays on military history. Through the World War II experiences of General Matthew Ridgway and the 82nd Airborne Division, we illustrate some of the similarities between the questions asked by officers of the 82nd yesterday and today—and dissect how they came to be.

I recently shifted strategy in writing. I imitated General Grant’s war making. I latched onto the enemy — in my case, the underlying concept to impart — and pursued it relentlessly, with little distraction. “The Blitzkrieg Defense” was the first series that ran on Ridgway’s Notebook. The Battle of Mook offered a stage to display the import of light, maneuverable battalions, and one officer’s skill at wielding them. Holding the reader’s attention to the nimbleness came at the expense of dulling the cause of the attack: artillery observation.

As a silent observer, I have been attuned for many months to dialogue on precision rockets and the dispersion their menace impose. My mind, supple as it is to tone and language, came away impressed that dispersion is a new phenomenon. And then one day I realized it is not. The last 23 years has been the anomaly — consolidated forward operating bases and motor pools. This is the frame of reference from which many approach contemporary writing on the subject of dispersion. FOBs and motor pools is not something Generals Ridgway and Gavin, or the Army of 1945, would have identified with. Dispersion is what they would have known. What imposed dispersion upon Ridgway and Gavin was the same thing that is imposing it yet again, aerial observation — a tool which precision rockets exploit.

As the 82nd Airborne’s attack rolled across Mook’s floodplain, the commander knew precisely what was happening in German rear area — roads thronged with ambulances — and observed cannon shells were raining down on pinpoints far beyond mere human sight. But how could this be without drones?

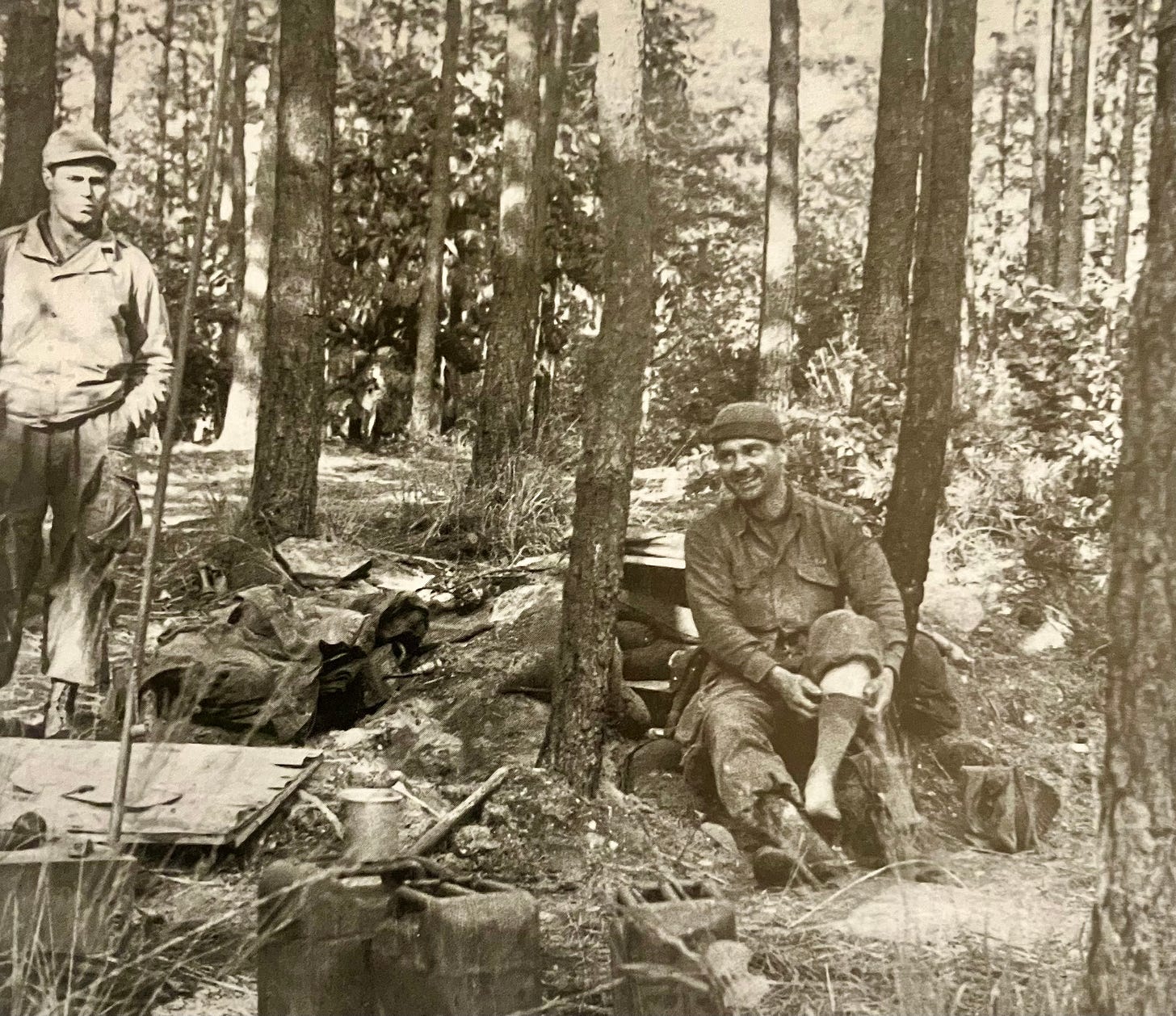

Overhead, a pilot in a small plane no more robust than a toy model, circled. German fighters were too scared to swipe at the little L-4 “Grasshopper” because at such low altitude, and with the swiftness of the Grasshopper, the offending fighter pilot was apt to drive into the dirt. Captain Bob Halloran of the 504th Parachute Regiment told his family that the Grasshopper was “one of the greatest weapons we have.” It was often referred to as an “Air OP” — airborne observation post — and could spot targets and smite them with artillery concentrations, and offer live adjustments with laser efficiency.1 The Germans had similar ability. And this imposed a level of dispersion and discipline — camouflage and log-covered dugouts — that is proliferating in Ukraine due to drones.

As an experiment, I tried to locate on aerial photographs the motor pool of the 82nd Airborne during the Battle of the Bulge — it was known through records to have been at Werbomont — and only a few trucks about the road were in evidence, all dispersed. The rest, I presume, were camouflaged and/or dispersed further. Anything bunched up was likely to be killed, even in early 1945. The offensive command posts displayed in a recent Military Review piece are not something that would have happened in the 82nd Airborne in World War II, especially at the regimental level.

Pragmatically, for the present, many of the principles the drone enforces will be a “back to the future” proposition along the FLOT. Opening the aperture, “Reenforced Winter 1” highlighted some of what dispersion meant to Gavin, and what it could mean in a division’s defensive fight in large-scale combat. Most are principles which have been good practice in the past; the nuance being he advocated for a capacity for all-around, active defense. In the attack, a challenge to the freedom of units to assemble are not new — look at World War II DIVARTY message logs.

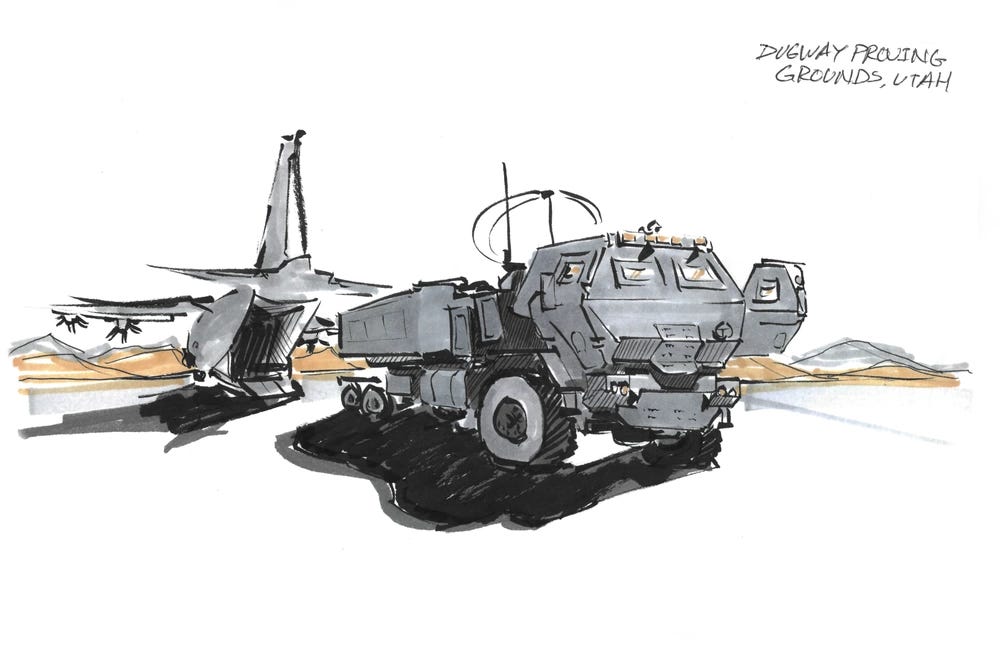

Yet, it’s quite clear things are changing. The object of the 82nd Airborne’s attack across the Mook floodplain, to push the Germans out of observation range of the Heumen Lock Bridge, may not be possible today due to the exponential increase in artillery range. What does that mean?2 But things like this, real change verses perception of change, can be hard to discern in recent writings. The language is sometimes slovenly, to employ the term Orwell did. Phrases like, “The character of warfare is changing,” is the multiplication of words without knowledge. Describing what is changing should be done with the same precision as the HIMARS rocket it describes. Otherwise, it’s a fist connecting with air.

📚READ OF THE WEEK📚

On “Reinforced Winter”

“Reinforced Winter: All Americans in the Battle of the Bulge” will continue as a rolling series. I have ideas and themes planned for future posts, but they need more research. I know this distinguished audience will appreciate the quality it will give, and also the time it takes to gather.

See They Called it Purple Heart Valley: A Combat Chronicle of the War in Italy by Margaret Bourke-White, Simon & Schuster (1944).

After I wrote this, B.A. Friedman published a piece which had a sentence that bears on this particular example: “The future of armor, at least armor cooperating with or moving infantry, will be long-range. It will need the legs to start beyond the range of enemy long-range precision fires, move through the range rings with a quickness, and hit its objective on less than one tank of gas or one battery charge. Fast-moving, long-range armored vehicles will be very difficult for even an advanced recon-precision complex to reliably hit.”

The FOB in the 90s - Forward Operating Base- for example Desert Storm - was logistics assets maneuvering. The LOGPAC was a full logistics resupply mobile column that emphasized fuel, ammunition and food/water.

Everything was MOBILE.

Our Depot level maintenance was MOBILE. Depot level maintenance for the reader is major repairs, 3-4 maintenance echelons back.

I was there I’m not making it up, I saw all of it. Also saw it practiced in peacetime exercises before and after.

Then came the War on Terror or something and we ended up with Colonial government by default - and so static.

By 2006 in Iraq “we went to war and Garrison broke out.”

“Forward “ became the Gate.

LOGPACs became fixed schedule supply runs between fixed bases hauling goods to the PX and shopettes , Burger Kings and Green Beans. The known, fixed schedule on the few hard roads supply runs were easily targeted and blown up all day and night long, with every movement transmitted on unsecured FM nets because the civilian vehicles being escorted didn’t have crypto. It was called The Sheriff’s Net and anyone with a civilian radio could listen in, as the checkpoints never changed it would take a dim lad indeed to not figure out their location.

I doubt I’m giving anything away here saying Checkpoint 59A was blown up every single night we were there-14 months.

This is the price of discipline.

Our discipline being that of the slave, not the soldier. I first wrote that in 2007, and anyone who counted knew it was me.

So in closing, in general maneuver is to be preferred to static, because if static your soldiers suffer and die to keep AAFES in clover 💵.

May I suggest if static allow no wire or barrier in rear areas?

This will keep people focused, because Fear you see .. isn’t the mind killer but the minds only real tool for perspective.

Otherwise War means Garrison breaks out.

Stay frosty. ☃️