Reinforced Winter 2: All Americans in the Battle of the Bulge

What the 82nd Airborne tells us about organization and attacking the defense of the future

Welcome to Ridgway’s Notebook, your home for airborne PME. We offer penetrating essays on military history. Through the World War II experiences of General Matthew Ridgway and the 82nd Airborne Division, we illustrate some of the similarities between the questions asked by officers of the 82nd yesterday and today—and dissect how they came to be.

Operations in depth expand the battlefield in ways that create greater numbers of opportunities and allow the division commander to control the tempo of operations and establish positions of relative advantage.

— FM 3-94, ARMIES, CORPS, AND DIVISION OPERATIONS (July 2021)

When Gavin struck out across the Belgian countryside, he did so at a dead run. Their second year of war started with unletting pursuit of the enemy. With the extra regiment, he was a quarter larger. Yet he was more unlimbered than ever. As he and his fellow senators of martial purpose — those notable figures of command — convened in 1946 to point the Army’s weathervane, Gavin would think back on those wintry January days. His purpose in overthrowing the triangular division was not only freedom in the defense, but for freedom in the attack. And although it was structurally larger, economy within its bowels gave it celerity and unfettered pursuit of the enemy.

While Gavin and Charles Billingslea wanted to stay fettered to the enemy’s heels, the effort in some of their fellow senators left them fettered to roads. The triangular division which had served them well was the subject of debate; many saw the conference as a path to improvement, not radical change. The improvements were to fight the last war with better and more. The quest for better and more food was stripping the truck of its lethality before Colonel Billingslea stood up.

My personal feeling is that we are bogging ourselves down with junk… We didn’t want the tanks and a lot of things down in there. Now we are happy to get trucks down there that are loaded down… with iceboxes. I say, if there has to be a certain amount of transportation, let’s make it fighting transportation and get rid of some of these unnecessary items. Men have lived on pocket food for a long time. In jump operations we went in with what we had in our pockets and existed and fought extremely well… I have seen organizations on my right and left time and again use the ‘A’ and ‘B’ ration — recommended here wherever possible — [and] stop in the middle of a combat operation to be fed. Maybe their morale was good, but while they were building morale, we were taking ground.1

January, 1945

“7 AM Everybody tense waiting for attack at 830.” Kenneth Nicoll was in the mud when he inscribed those words in his diary. His nondescript hole was designated an “observation post” despite its striking similarity in rawness to every other hole of the line. His observation was of Floret, an agrarian hamlet set about the soft green hills. This was Colonel Fowler’s objective when he jumped in Nicoll’s post to observe the attack. Nicoll would be a spectator as Fowler’s tank men ran at the village on which many paratroopers teeth had been gnashed. General Gavin was saving Nicoll’s toil for another task.

Fowler’s tanks roared, artillery poured, and Germans filtered back in a captured state. Nicoll’s modest contribution was spotting 81 mortars as they stitched a tree line. “Dark and the 504 is pulling out for unknown destination,” Nicoll inscribed.2

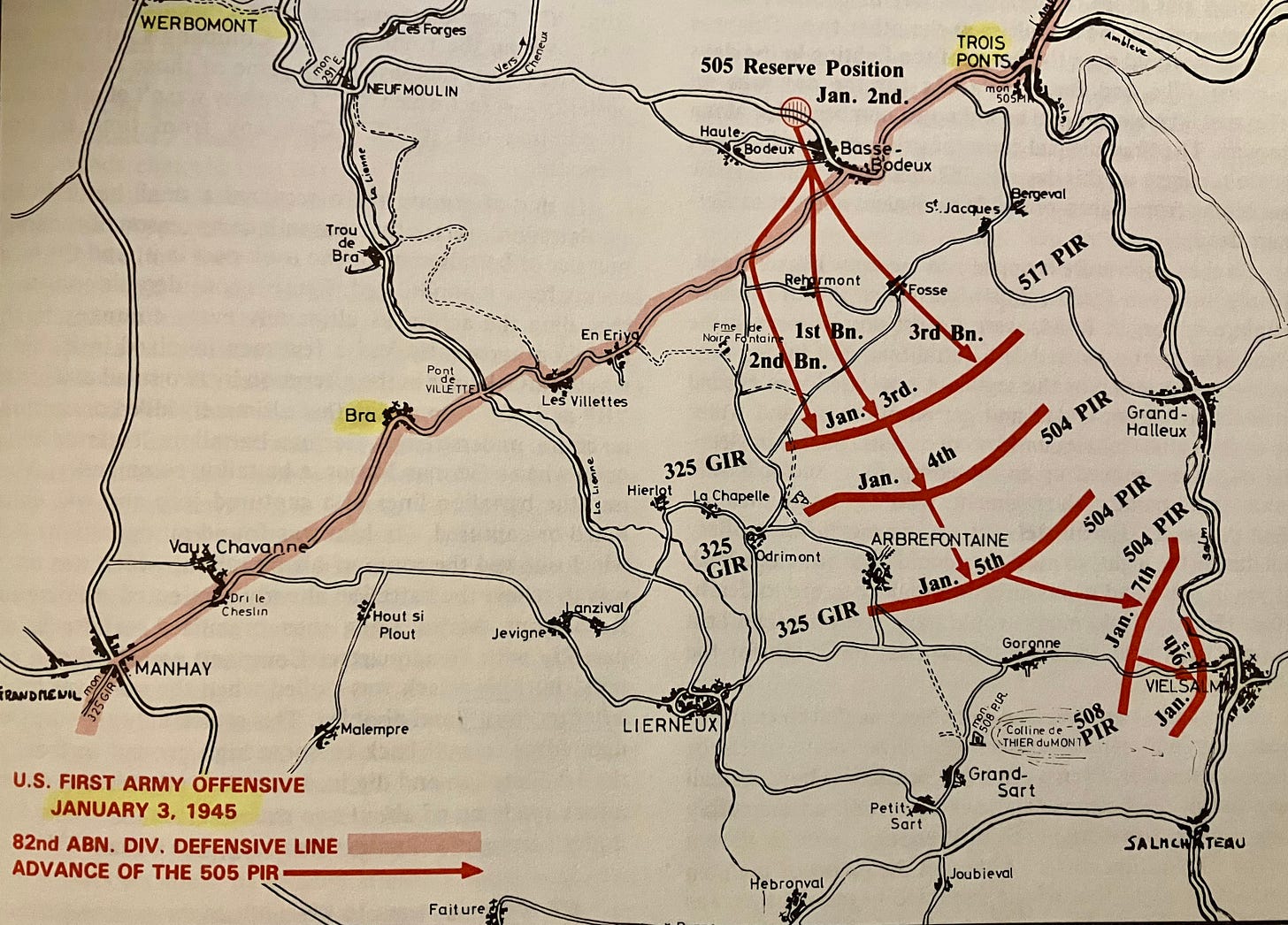

The view from Nicoll’s observation post that January morning was a modest one; not even the lowly lieutenant knew where he was destined. But from the command post the view was ambitious. The gears which set the division into motion were churning. Like stage hands preparing for a set change, units of men were in choreograph moving to and from assembly areas and attack lanes. In the defense, General Gavin had used his square division — that is, a division of four regiments — to fight in four directions. Now he was going to use it as a rolling barrage.

Under the standard triangular formation, depth, endurance, and direction were not as great as they could be. Gavin planned to send his first two regiments out to attack for 24 hours to ground the enemy defenses. The other two moved to assembly areas charged to march on command. He had as many attacking elements as reserve elements. At 2 or 3 AM the next morning, Gavin would pass the two fresh regiments through to take up the attack. Whether the Germans were holding or in flight, Gavin had the endurance and range to keep pounding, and balance to fight in another direction. It had the effect of always having two attacking elements — a force the triangular division couldn’t generate — and if he needed an assault regiment, he just fed one artillery.3

And so Gavin struck out across the country on January 3. The 505 battled vigorously for Foose; the 325 for Andrimont. These scraps were distinguished in their tenacity. A tank battle developed in Andrimont, and in Foose the Germans were entrenched and dug out through willpower. But as Corporal Earl Oldfather struggled to roll his pack in the confines of his hole, the die was being cast for the pursuit. Out ahead of him, the two attacking regiments fought the terrain. They chopped the countryside up in phase lines, moving abreast, taking one at a time like segments of an ant. In their wake, Oldfather and the 504 would follow.

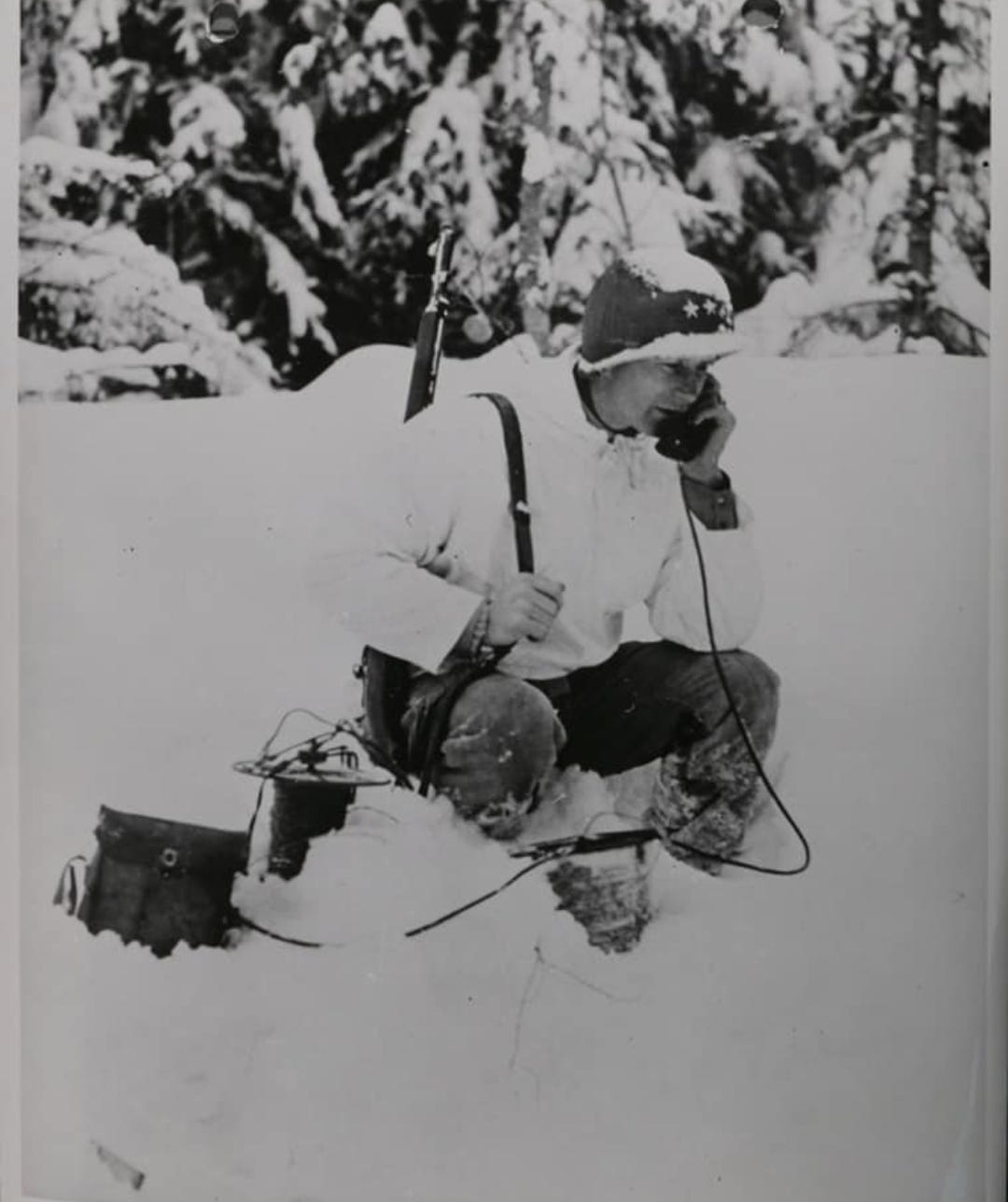

They moved under darkness, and through a driving snow for two days. Fatigue overtook Nicoll and Oldfather alike as the stoic power of the rolling hills conquered them. Nicoll, veteran of Italian mountain campaigns, remarked to his diary, “We climbed the steepest and slippist [mountain] I ever saw. It was snowing to top it off. My men are exhausted, but we have made it to the top.” The cold bit and snow piled into drifts that dwarfed man in spots. Walking was an olympic exertion.

As the 504 passed into attack, they broke the shackles tying them to the roads. They nosed down firebreaks piling all superfluous equipment, bedrolls included, and were swallowed by the forest naked to face the cold.

During the route march, some of the most frustrating places to walk were the main road. Truck traffic had hammered snow to sheets of ice making it treacherous in spots. Roads and firebreaks — most important in the 504 and 505 sectors — were rendered impotent. And those that weren’t were so constipated “it was an accepted thing to take [vehicles] through minefields when traffic became too congested on the roads,” the division ordinance company reasoned.4 Ammunition had priority, followed by food which was often tardy. While other units may have had “high morale” the All Americans were taking ground.

Lightness was seeing them through. Even though the division was a quarter larger, Gavin had his thumb on the scales. There was plenty of teeth and just enough tail, and in only the right places. His medics had jeeps, the regiments and quartermasters utilitarian duce-and-a-halfs, and for artillery, motors to tow the guns. There was little fat, the truck was a military weapon — there were no iceboxes or command posts on wheels. They were not bound to the road, which gave them the speed to ensure the enemy got no reprieve and allowed them to go anywhere. On January 7, in the final act of the attack, a German battalion sent to relieve Foose — three days in friendly hands — was rolled up and cut to ribbons.5

The two principles — symmetry and lightness — married at Thiers du Mont Ridge, that natural citadel they had once held.

On January 7 the cast would act out the design of the conductor. The 504’s trite muscles overtook the attack for the final exertion at the Salm, and the 508 would pass into the attack on the heels of Lieutenant Colonel Osmund Leahy. A rolling barrage of legions, new hammers to fall.

Back in Andrimont the first day, Colonel Leahy’s men absorbed a swatting by German tanks and had been attacking since. But as they attacked this final day, they would meet German tanks again to bookend their breakout.

The division’s commanders had a mixed feeling about the American tanks which had supported them. In the heavily forested 504 and 505 lanes they were of little help, some even seeing them a burden, but in the 325 lane where roads were more robust, they had more utility. As they bit segments off the ant, paratroops were a step ahead of the armor. They seized the high ground and road junctures and held the curtain open. At Andrimont — “hot as a two dollar pistol,” according to Leahy — they helped deal with German self-propelled guns and 20mm cannons.6 From then on, they were often only able to generate patrols where the paratroopers’ were already in strength owing to their lightness.7

In this culminating act, the tanks would be held on call, and Colonel Leahy’s men would serve as the spearhead. But in the conduct of the attack, they would execute Gavin’s design — in Leahy’s wake would come a battalion of the 508 passing out of reserve. When the engagement required it, they would overtake the attack and pass through Leahy to bear the arduous task of assailing the high ground. At Thiers du Mont, all the details that made the division attack successful met to compose a wholesome chorus of combined arms. The summary of Leahy’s combat interview reads like the sheet music.

It was dark when the attack began, the terrain was hilly and wooded and everything covered with a blanket of snow and ice. It was bitterly cold. The first resistance was encountered from a focal point, which Colonel Leahy estimates to have been an outpost. At first light, that is about 0730, Company K was on its objective - the ridge - while Company I had reached the saddle between the ridges. Colonel Mendez, CO 3rd Battalion, 508th, was following… and planned that when [Leahy’s men were] in the saddle, he would proceed to Menil and use the hills overlooking the saddle for protection to do so… To do this radio communication between the two battalions was synchronized and coordinated. Up to this point resistance had been light. Colonel Leahy had left a squad of tanks and a platoon of men at Abrefontaine at which point they were on call, and at 0715 he called for them to come up. This was necessitated by a heavy volume of machine gun fire from well dug-in positions on the north side of Thiers du Mont and also from several tanks in the neighborhood. The saddle is about 800 yards wide and perfectly open… Company I was in the saddle and pinned down and Colonel Leahy went to see what was holding up the advance… While he was there a German tank fired point blank into I Company and 5 men just disintegrated. This had a disorganizing effect on the company which he then ordered back into the woods to the west and behind Company K. He did likewise for Company L. He then planned to go off the east edge of the western ridge, thereby coming in on the battalion objective, Grand-Sart, from a northwesterly, rather than northerly, direction.

There was great danger that the Germans who had direct observation on his position could see his movements and move in behind. This danger could be obviated by the appearance of the armor. The squad of tanks arrived and as they came along the road, a Mark VI opened fire and in three shots knocked out two TDs. The remainder of the armor never did appear. Colonel Billingslea tried in every way to get the armor to come and he asked Colonel Leahy about other ways rather than giving on the main road. [Colonel Billingslea in his own words said the Germans “raised holy hell all around the place.”8]

In the meantime, Colonel Mendez also pulled back into the woods to the west. There are two ridges here, Thiers le Preux to the west on whose eastern slopes and woods Colonel Leahy had sheltered his battalion, and Thiers du Mont to the east. In between in the saddle where both Colonel Leahy’s battalion and Colonel Mendez was heavily shelled. Colonel Mendez had a conference with Colonel Leahy and news was received that 3rd Armored Division’s tanks were coming in from the west through Menil… The 3rd Armored was moving up but the enemy continued to shell the 325th and 508th from its positions on Thiers le Preux, inflicting heavy casualties on both regiments. The shelling lasted from approximately 0800 and 1200. By that time, the 3rd Armored was moving in from the west…9

At this very moment, Mendez attacked across the saddle with his first company. The German observation was acute — three to four shells were fired at each man who dared move. It took an hour and a half for them to infiltrate the mere crest. At this time, the rest of the battalion rushed the saddle and assailed the hill, carrying the assault through. As they raced down the ridge the Germans rapidly collapsed. Captured was a half track, two tanks, three vaunted 88’s, six artillery pieces, and six assorted vehicles — and 119 prisoners for good measure.10

In basic battle drill, there was nothing revolutionary. But to allow for the toil of the battalion to endure, good division design was needed. Therein lies the revolution. Gavin wed to a division light in its bones and broad in its girth, with four regiments. Its weight birthed speed and utility to fight off-road; its square symmetry, balance and punch. It turned Gavin to Grant: he latched onto the enemy and didn’t let go.

Unfortunately we had little opportunity to see a 4 regiment division fight offensively. I know of two that fought that way and fought well… In fighting against the defenses of the future, and they are going to be very fluid with as much likelihood of attack in your rear when you are in the attack yourself as from the front — you must be balanced and be able to fight in any direction.

— MG James Gavin, 1946

Report of Committee on Equipment and Supplies, The Infantry Conference, June 1946.

Nicoll, K.S. Diary. Entry 3 January 1945. LTC Paul Fowler was the commander of 3-36th Armored Infantry.

Minutes of the Infantry Conference, Committee on Organization, 1946.

“Unit History,” 782nd Airborne Ordnance Maintenance Company, 15OCT45

Combat interview of William Ekman (CO, 505th PIR)

“3rd Battalion-325th Glider Infantry.” Combat interview of Lt. Col. Osmund A. Leahy by Major J.F. O’Sullivan

Compare the sequence given in the 3AD G-3 supplement of Spearhead in the West to Billingslea’s combat interview.

Combat interview of Charles Billingslea (CO, 325th GIR)

“3rd Battalion-325th Glider Infantry.”

“German Breakthrough.” Combat interview of J.W. Medusky (S-3, 508th PIR).

I can't even imagine how they were able to fight in this cold. It's something that I think about every time I read about Bastogne. Good read and thanks for the map. It was helpful.

Gripping read, masterful in understanding the 82nd on the attack