To paraphrase a statement by General Gavin, “If our development of equipment for amphibious warfare were as backward as our development for airborne warfare, we would have landed on Normandy and Iwo Jima in rowboats”—or rather we would have never landed.

—General Lewis Brereton (USAAF), First Allied Airborne Army

Successful airborne operations rely on close cooperation between airborne units and their Air Force counterparts. This was never more true than in WWII, when technology available meant training and close liaison with the airborne was paramount. Major General Matthew Ridgway could see this; why could so many others not?

Let's look at how Troop Carrier Command's evolution, from the debacle over Sicily in 1943 to the near perfectly executed operation into Germany in 1945, helped shape how the most famous operations of WWII happened.

We can look as far back as November 1942. The first time US airborne forces were dropped into combat, and much was learned from this disaster. Paramount was the principle of carrying a fighting force over such a vast distance (the flight route was from England to North Africa) without having a navigator aboard each aircraft. This problem persisted in Sicily, and this, coupled with less-than-ideal weather conditions, resulted in the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment being scattered all over the Island. It began a chain reaction: the alteration of flight paths for day two resulting in one of WWII’s most devastating friendly fire incidents. For Ridgway, this could not be allowed to happen again.

Criticism of Troop Carrier performance over Sicily is often quite strong but often unfair. Navigators were still low in number in the troop carrier groups. It was not only one of the most intellectually challenging roles in the Air Corps, and one not suited to a great many, but of those who did graduate from the Aviation Cadet programs as navigators, most found themselves assigned to bomb groups where every aircraft required a navigator. This meant that by Sicily, as few as one in six C-47s carried one. When the weather plays a hand in an operation, most aircraft lack the capacity to recover.

After Sicily, Ridgway made several comments in his report indicating he recognized that part of the issue was related to the amount of training airborne forces had with the troop carrier groups which were expected to deploy them.

Profiting from the lessons learned in SICILY, he repeatedly and vigorously urged a minimum of three weeks combined air-ground training with the Troop Carrier Command. He urgently recommended that the 82nd be immediately concentrated in the KAIROUAN area for the purpose of re-organization, re-equipping, and training.

The fundamental problem with war and the need to build, train and deploy forces quickly is that it results in deploying various forces long before they are ready. This was seldom better demonstrated than with the troop carrier groups used in airborne operations from November 1942 to July 1943, and perhaps beyond. To understand this, all we have to do is look at how the Air Corps expected the war to go. Troop carrier groups were low on the list of requirements, as was the mass construction of aircraft suited to the role (the C-47 did not fly for the first time until two weeks after Pearl Harbor.) The USAAF was focused on the development of bomb groups that would simply bomb the enemy into surrender. When the Air Corps finally realized that putting boots on the ground would be as necessary (as in previous wars), airborne and troop carrier units were hastily assembled. Troop carrier groups (TCG) were being sent overseas having dropped an actual cargo of paratroopers on as few as two occasions.

At the same time, a lack of assault gliders meant that for Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily, the 82nd Airborne would have to fight with one arm tied loosely behind its back as it could not turn to the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment, who remained in reserve throughout the campaign. Even by the time of the invasion of Italy, a lack of gliders meant that glider infantry had to be landed by sea. This problem persisted beyond “D-Day,” or Operation Neptune, in June 1944 which impacted how the two US airborne divisions were delivered in Normandy.

Normandy

Cue preparations for D-Day and a change in tempo. When the 82nd Airborne Division arrived in England in early 1944, they were stationed in the Midlands region with the trooper carrier groups of the 52nd Troop Carrier Wing. Though it cannot be confirmed through official records, it is likely that the two units being so close to each other was no coincidence and that the continuation of that partnership would have been very much at the request of Ridgway. Despite what authors like SLA Marshall and Stephen Ambrose might have you believe, training between the airborne and the TCGs was intense in the run-up to “D-Day,” with no fewer than 33 combined air–ground exercises being carried from the beginning of March to the end of May. Other exercises organized below the Command level were carried out with the airborne units, and the training schedule Ridgway had longed for finally came to fruition.

IX Troop Carrier Command, as it was now known, had grown massively in size since the invasion of Sicily and now contained fourteen TCGs capable of bringing to bear on the enemy over 1,200 C-47's, 1,100 CG4A “Waco” gliders, and 300 of the British-built Airspeed Horsa Gliders. The latter was made necessary by the continued lack of Wacos. There were too few to carry the glider elements of both airborne divisions to Normandy despite a vast assembly facility having been built astride RAF Greenham Common.

With the division of gliders split equally between the 82nd and 101st, it meant each was allotted fifty gliders for D-Day’s initial lift. Because of the way the ground plan for the divisions was developed, in real terms it meant that Ridgway’s 82nd Airborne would land with no artillery support. Thus, Ridgway argued the gliders be reallocated from the 101st to his 82nd.

For the 101st Airborne Division, this had the bigger impact as it meant they had no choice but to send their 327th Glider Infantry Regiment in by sea via Utah Beach on D-Day. For IX Troop Carrier Command and the airborne divisions, the apparent priority was getting all of the parachute elements down in the darkness hours of June 6th, leaving just two groups capable of towing gliders that early. The 437th and the 434th Troop Carrier Groups had deployed 104 CG4A gliders by 0410 hours on D-Day. To offset a shortage of Waco Gliders, the Horsa Gliders, which had a bigger carrying capacity, were brought in to allow them to deliver all of the glider infantry and glider artillery of the 82nd Airborne on June 7th after aircrew that had flown the paradrop the night before had had a chance to recover.

The reasons why Ridgway won the glider allocation argument seem reasonably clear. The 101st operated closer to the invasion beaches, meaning the 327th could be with their division and in the fight much quicker. It was this line of thinking that Ridgway used in his argument. The 325th Glider Infantry Regiment, one of only two regiments across both divisions to have seen combat before, was not given an assignment for the operation and was Ridgway’s reserve. This allowed Ridgway to send them where they were most needed once on the ground. (They were eventually sent into the fight for the causeway at La Fiere.)

The 101st Airborne Division takes in one artillery battalion by parachute, which will be available to it in time to participate in the attack eastward… The 101st Airborne Division can shortly thereafter count upon powerful air and artillery support, the latter from guns on the beach and aboard ships.

The 82nd Airborne Division, if its glider lift is not increased, will have no artillery whatever, nor any artillery support from other units in the corps until daylight, D+1, at the earliest.

It seems obvious therefore that the heavy weapons capacity of the glider lift now assigned to the 101st Airborne Division is desirable for that division, but imperatively necessary for the 82nd Airborne Division.

—Ridgway to GEN Bradley in a TOP SECRET memo dated May 11, 1944

The impact of a shortage of gliders was not too significant when it came to the operations in Normandy, as forces brought in ashore could be with their division reasonably quickly. For later operations, however, notably Operation Market Garden, the inability to deploy entire divisions in one day was noticeable and significantly influenced the fighting. This was in part due to the size of the operation and the necessity for nearly all of the parachute elements of the British 1st Airborne Division to be carried in on American aircraft. This put a considerable strain on IX Troop Carrier Command, who again had to focus on delivering the parachute elements of Allied Airborne Army before turning to the gliders.

Gliders were now much greater in number but did, of course, rely on a tow plane and the crew to fly it, and this left both divisions operating at much less than 100% for several days. Again the 82nd Airborne Division had to operate in the early stages without the 325th GIR, amounting to nearly a quarter of its infantry, because a lack of tow aircraft and poor weather conditions caused numerous delays.

Continued development in the aircraft that IX TCC could call upon demonstrated that the US Army Air Force was still seeking to achieve the “perfect” large-scale airborne operation. By March 1945, this was just about achievable.

There were two changes: The first was the introduction of the Curtiss C-46 Commando, a massive twin-engine transport aircraft capable of dropping twice the number of men than the C-47 by having jump doors on either side of the fuselage. The 313th Troop Carrier Group transferred to the C-46 in 1945, meaning it could deploy an entire regiment of paratroopers instead of just two battalions as was typical for a group operating C-47s. The second development was the introduction of the double glider tow in Europe carried out during operation Varsity by the 439th Troop Carrier Group. The double tow meant that more gliders could be brought in one lift using half the aircraft. But it was not easy to achieve.

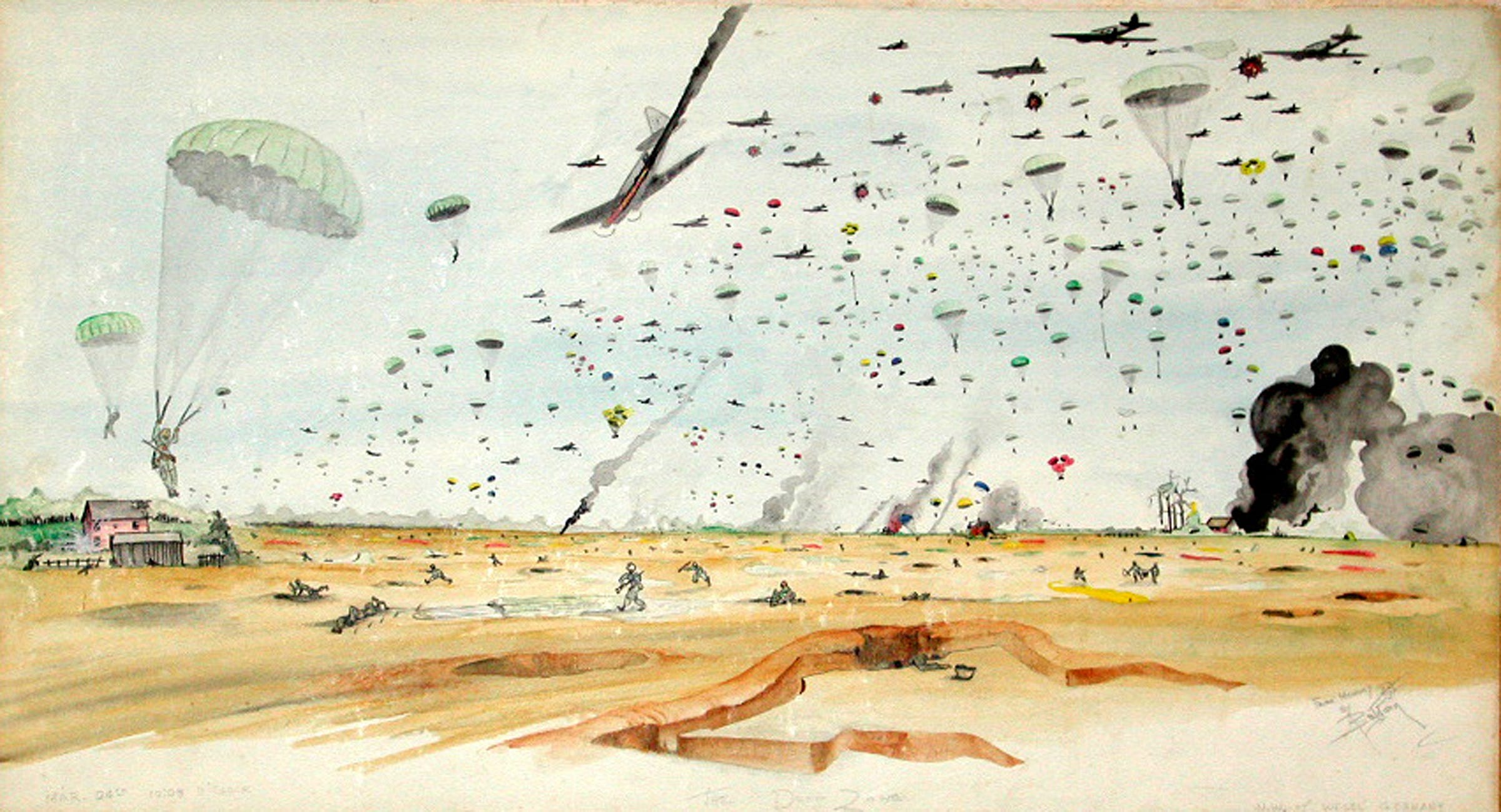

Unfortunately for Curtiss, the C-46 proved to be incapable of sustaining the damage one would expect an aircraft to receive on a combat operation, with 19 of 72 aircraft shot down. Critically, however, Varsity has gone down in history as the largest single-day airborne operation in history, with two complete Allied airborne divisions dropped in one day. It is considered by many (including General Gavin) to be a true reflection of how a large-scale airborne operation should be carried out.

—

Adam Berry is an English historian. He is the author of A Breathtaking Spectacle, focusing on IX Troop Carrier Command in England. Follow him on Twitter: @Agrbez.

Upcoming posts:

The Blitzkrieg Defense: The Battle of Mook Part 2 - The Kiekberg Drama

Sharpening the Talon