It is the eternal quality contained in the best literature of the First World War… that invests the experience of the Somme with the importance it continues to hold. Nothing which the Second World War evokes stands comparison with it (though a few unfairly overlooked novels of remarkable depth have been published: in England David Holbrook’s Flesh Wounds, in America James Jones’s The Thin Red Line).

—John Keegan1

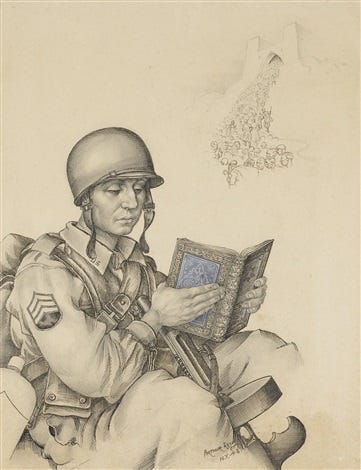

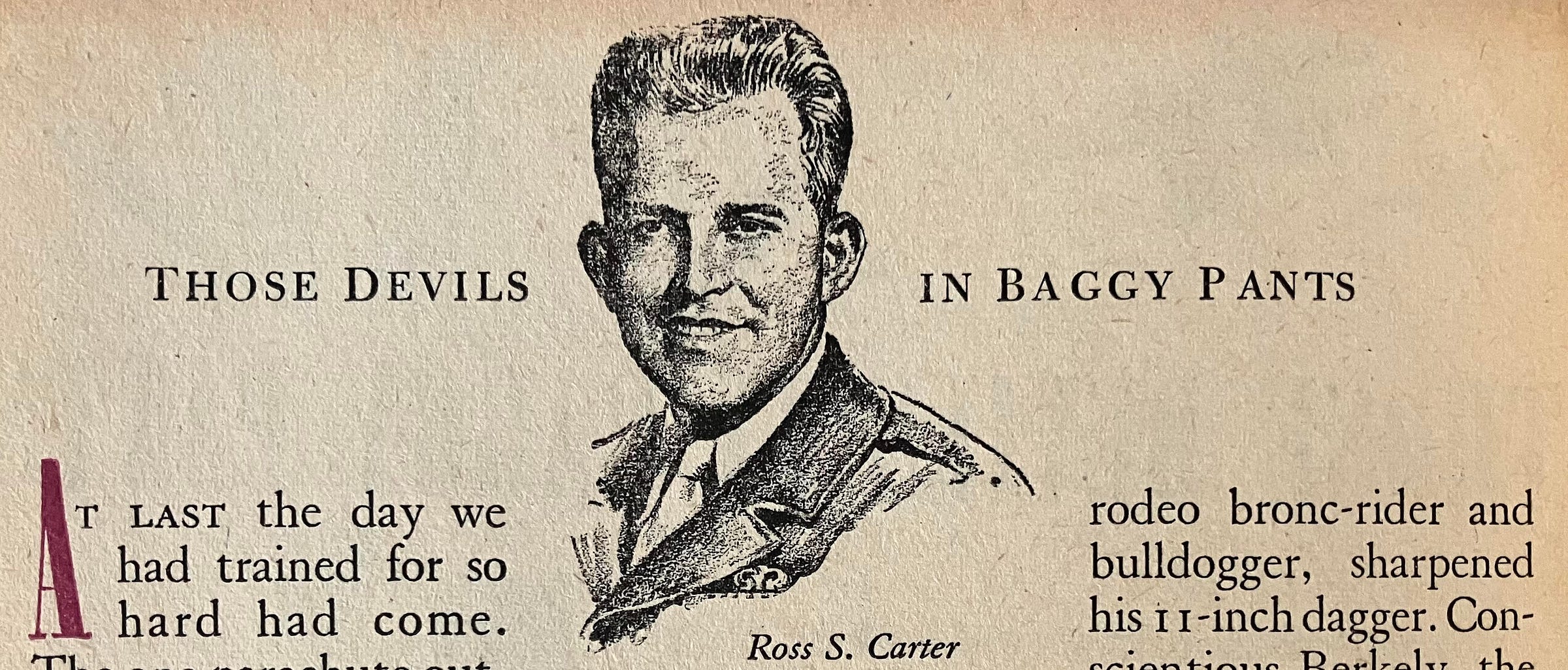

Those Devils in Baggy Pants catapulted Ross Carter to the most famous soldier of the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment. Now that his comrades are (nearly) gone, his literature is the last place to engage the intangible soul of the “Legion” to which he belonged. In this way, as time marches on and we remove ourselves further and further from those devils in baggy pants, Ross Carter will become the 504th Parachute Infantry.

Perhaps it was always meant to be this way…

Who is this man, then?—this “man who is the regiment?” Little can say more about him than his work. Ross Carter’s approach to war is immediatly distinguishing from his veteran-literist contemporaries. Populust war literature such as Flesh Wounds, The Naked and the Dead, The Thin Red Line, or essays by Paul Fussell, were written by men who illustrated how war destroyed souls, how they were resentful of their circumstances, how futile bravery is (or the importance of self-preservation), how the Army didn’t prepare them, and how they were angry.

Ross Carter’s book includes fatalism, because it’s true, but it was not written by an angry man. Where these men saw futility, Carter and his companions were convicted to a cause and to one another. It will hit you where it hurts, but Those Devils in Baggy Pants will leave you proud that America produces such men. Men who endure, triumph, and win the crucible. Men who bend but never break, and never ask for quarter owing to their intense pride.

The feelings evoked by his prose reflect the author’s true character, even outside his literature. Shortly after Ross Carter re-enlisted in the Army, he found himself disgusted by complaints from overseas occupation troops. They induced a response built by Carter’s pen. The “People’s Column” in his home newspaper published his editorial:

The United States Army spent several years proving to the world that they have the best fighting men in the world. It became a byword in every country that the United States Army could accomplish the impossible. The men composing the army did a bang-up job of winning the war. Their courage, discipline, hard word, and cheerful acceptance of tough conditions forced respect from the enemy as well as friends.

As soon as the war was over, the cream of the United States Army came home and got discharged. This was their reward for their devotion to duty. They earned this reward and they got it. These men were the guys who left this country soon after Pear Harbor, and stayed away for two, three or four years. They deserved to come home, for they had walked in bloody sacrifices for a long time.

They were replaced with soldiers who had seen little service in the army, or who had seen very little combat. Reasonably, it was to be expected that occupation forces would continue their bangup job in the same spirit that the fighting men had fought the war.

However, from the occupation zones, there can only be heard a continual whining. Gripes, howls, beefs, there are stronger words for it in the army lingo. These young, tender, kids are moaning to come home. They didn’t win the war, they have no artillery and mortar fire to face, they get three squares a day, they sleep indoors every night, their military duties are slight, but they stage mass meetings contrary to army discipline, and they are making nay, have they made the United States Army the laughing stock of the world.

Overseas duty, to a man who would rather stay in America, is never a picnic. However, we need men to guard the peace abroad. A number of citizens in this country want our troops removed from the zones of occupation. Well, we removed out troops after World War I, and look what happened. We’ve got to have somebody to guard the Germans and Japs, and who could be more logical as guards than the guys who didn’t have to fight the war: Yeah, I mean the green troops that are overseas now.

To veterans of Africa, Sicily, Guadalcanal, D-Day, Okinawa, this whine of the occupation soldiers stinks to high heaven. Those whiners should thank God that they are in the American Army rather than in many foreign armies… in those armies whiners would receive severe treatment.

If I fought through six campaigns without whining, surely these guys can solider a year or two in peacetime without raising their voices to high heaven. Yeah, you guessed it, I’m going back to Germany, and listen to those kids whine.

S-SGT. ROSS S. CARTER,

U.S. Army Paratroops

Bristol, Virgina2

It’s a terse example of Ross Carter’s fibered, sacrificial character, which is veiled within the person of “the Arab” of Those Devils in Baggy Pants.

And Carter’s intellect was as fibered as his character. Before the war, he lived in a dairy barn for a spell while majoring in history at Lincoln Memorial University. He graduated Cum Laude. For a young man of his station, Carter was unusually well-read. In Those Devils in Baggy Pants, works as contemporary as Hemingway and as ancient as Homer and Latin itself make cameo appearances through the reading habits of Carter and the Arab. Through the Arab, Carter would refer to himself as a modern Ulysses.

I have written this more as a history of the regt. because Ross Carter was the regt. He, and men like him. You can substitute his name for the 504th.

— Frank Dietrich

In the war, nobody knew Ross Carter’s character better than Frank Dietrich. Carter became acquainted with this stout Michigander in May 1942 when they were at Fort Benning’s jump school. It was the start of a three year odyssey they would share. At the end, only Cater, Dietrich and George McAllister would see Germany with the platoon they joined. Dietrich had an intimate view of Carter’s character under circumstances which are the most revealing trial of the subject.

As for [Carter’s] war record, it would take many pages and could not be written in weeks. I will try to give you a brief account of it… After Ross was assigned to the 504th, he stayed at Ft. Benning until the fall of 1942. The 504th moved to Ft. Bragg, NC then. About Christmas of 1942 Ross was made corporal and platoon radio operator.

The 504th stayed at Ft. Bragg until about the first of April, 1943, and from there was sent to Camp Edwards, Massachusetts, to prepare for overseas shipment. The 504th left the States on April 29, as part of the 82nd Airborne Division and landed at Casablanca, North Africa, May 12, 1943. From there the 504th went to a small town in central North Africa to take extensive training in a combination of desert-mountain warfare. On July 11, 1943, the 504th jumped in Sicily. Ross was part of the 1st and 2nd Battalion combat team that was shot down by our naval and anti-aircraft units on the ground… The 504th stayed in Sicily for 38 days and completed part of the history that the 82nd Airborne has.

The next combat for the 504th was at Salerno, Italy, about September 1943. We jumped there and have been credited with playing a large part in saving the 5th Army “beachhead.” We fought up the coast and were part of the first troops to enter Naples, Italy. The 504th stayed at Naples for about a month. During this time Ross became a Sgt. Then the 504th and Ross moved out for the Volturno River, as shock-troops, traveling in trucks instead of planes. For two months they fought in the mountains and then were pulled back for a very short rest. The next combat took place on a mountain 3600 feet high, numbered 1205. This action was a Cassino, Italy, for a period of two weeks before and a week after Christmas, 1943. It was here that Ross received the Silver Star…

Then the 504th was relieved and pulled back to a small town near Naples. From there the 504th moved by boat to Anzio and fought there for 69 days of this “Hell Hole” of a front. The 504th suffered many casualties throughout the entire fighting in Italy. But Anzio was one of the worst places that the 504th ever fought.

The latter part of March 1944, the 504th left Anzio for Naples. After two weeks there they set sail for England and arrived sometime in May ’44. The high command decided not to use the 504th in Normandy, but to hold the regt. in tactical reserve.

The next combat for the 504th was the jump on Nijmegen, Holland, on September 17, 1944. The regt. fought in Holland until relieved by the British in November 1944 and was then moved to France for a rest and to prepare for a mission. The regt. stayed at Sissone, France until the enemy tried to break through in Belgium. On the 17th of Dec. 1944, the regt. and the 82nd were moved by truck to the St. With area in the “Bulge.” The night of the 19th was spent in an attack that never produced any enemy. The night of the 20th the 1st Battalion suffered 300 casualties out of 360 men. Ross was wounded very seriously in the right arm. He was evacuated with the other wounded to Paris and then on to England. This action in which Ross was wounded was the first time that von Runsted had been stopped in his dash across Belgium. Not only was he stopped but was turned back.

Ross returned to the 504th from England about the last of February 1945. He stayed in Laon, France until about the middle of April and then took part in the dash across German to meet the Russians. He did meet them across the Elbe River in Germany, and was there when the war was over. Shortly after he returned to the States, arriving sometime in June 1945, and received his discharge on the 20th of June, 1945.

He had taken part in the first “beachhead” in Europe, and had also taken part in the last one, Sicily and the Elbe River.

Ross Carter had no enemies in the 504th. Everyone who knew him respected him as a friend and a soldier. He was a giant among men where courage and ability to lead men was commonplace. He will never by forgotten by any man that ever came in contact with him. I have written this as a history of the regt. and Ross Carter. It would be the same if the regt. were never mentioned... Ross has about 340 days of actual combat. A record that can be equalled by very few men who served in the Army.

I have written this more as a history of the regt. because Ross Carter was the regt. He, and men like him. You can substitute his name for the 504th. I hope this will give you the information you desire. I do not like this job and would give anything not to have to write it. Ross Carter is my friend.

Dietrich did not like the job because it was a eulogy. At the time he wrote those words, Ross Carter was near the end of a slow passage into death. Upon his re-enlistment, Carter rejoined the 504th. In the summer of 1946, Carter was enroute to Alaska with the airborne element of Task Force Frigid, an experimental unit he volunteered to join for testing the limits of men and equipment in arctic conditions, when a mole was removed from Carter’s back. Carter made one jump with T/F Frigid before he had to be releived. He made his way to Walter Reed Hospital, where he slowly died of skin cancer. It was here he gave Dr. Boyd Carter the final instructions for editing Those Devils in Baggy Pants.

Above: Footage of T/F Frigid in Alaska. The T/F was built around a company of the 505th PIR.

Ross Carter died on April 18, 1947 with Ms. Marie Niehaus at his side. Frank Dietrich was at Ft. Benning when his best friend departed. Ms. Niehaus wrote him the news. He replied:

Words are futile at a time like this. I can only say, and I’m sure that I speak for the many men who knew Ross, that, though he is gone he is not forgotten. The name of Sgt. Ross Carter will live on in the memory of the men who have fought and bled with him. When they take the measure of a man they will mentally check the qualities against those of Ross Carter, and if the said man can meet the said qualifications, he will truly be a man.3

📚READ OF THE WEEK📚

Join us next Saturday on Ridgway’s Notebook for:

“The Ulysses of the Parachute Infantry: Ross Carter on Hill 687”

John Keegan, The Face of Battle: A Study of Agincourt, Waterloo and the Somme. Penguin Books (1978). P. 288

Ross S. Carter, “People’s Column.” The Bristol Herald Courier. January 20, 1946.

Frank Dietrich to Marie Niehaus. Letter, April 25, 1947. Ross Carter Papers, Carnegie-Vincent Library, Lincoln Memorial University. The author is indebted to Ms. Rachael Motes for her assistance in digitizing some of the material from the Carter Papers.

Very interesting man. Looking forward to next week. Nice work.