The novelty of Iwo Jima’s volcanic rock, black as coal, was flushed out by America’s geography. The Marine deposed on the Pacific island would have identified stronger with the battlefield of his brother. Europe, like their home, was of continental expanse. The soldier there was largely planted on his feet and in his tank. To Iwo Jima, the Marine was deposited over the shore, coughed up from the bowls of a boat. Across the Pacific, each new invasion began feebly on a strip of sand. However, one likeness between the two fields of battle was that American men would be maimed on their grounds, and they had to be evacuated.1 It was almost the only likeness I was expecting when I cracked the pages of Surgeon on Iwo by Dr. James Vedder.

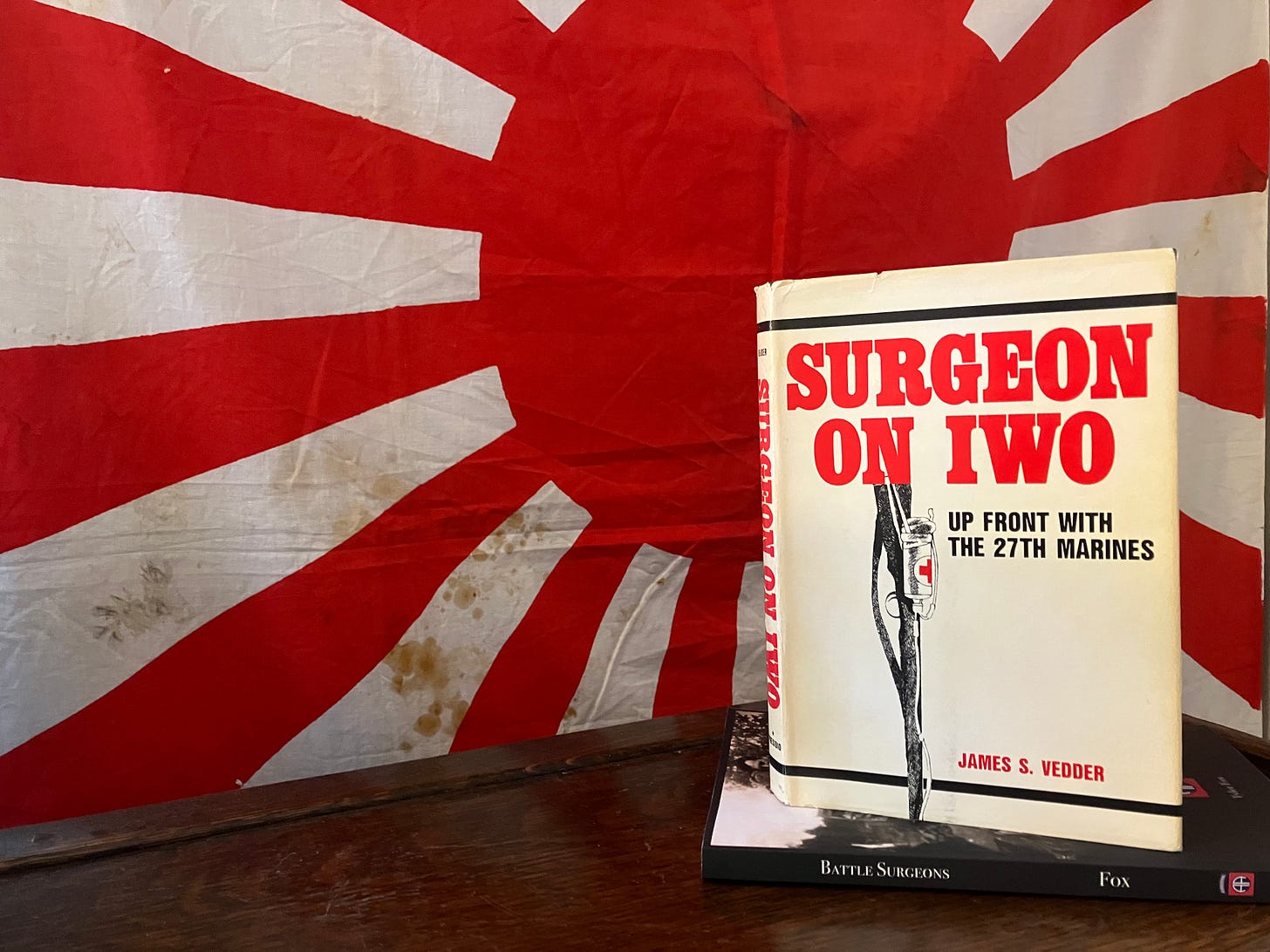

Surgeon colors the innumerable frictions of providing care at the bleeding edge of clashing civilizations. The book fortuitously fell into my lap. I happened across it in Maine, in a frigid garage of heaping book piles — overwhelmingly military — stretched floor-to-ceiling. The blood red SURGEON on the spine captured me. I had just concluded a two year study on the topic. “My” surgeons, however, had fought on the continental expanse of Europe. I opened Surgeon on Iwo anticipating that Dr. Vedder faced vastly different frictions on a volcanic island than the ones “my” surgeons faced on continental Europe.

I found much more alike than not.

Battle, this celestial force, produces certain traits no matter if the maelstrom befalls a continent or an island. Confusion is there. Disorganization is there. Therefore, Dr. Vedder treated a lot of Marines in his battalion aid station that were not from his battalion. His casualty book showed only 546 of 794 patients were from his own unit. These are large numbers. And Dr. Vedder had a large aid station — twenty-four men and two doctors. This caught my attention. I wondered if it was unwieldy.

On D+1, in midst of cataclysm, Vedder’s aid station — often just a shell-hole of some variety — had to move closer as his battalion pushed forward. With casualties lying all over the aid station, it forced him to split into two sections. Half would move to provide close-in support to the battle line, the rear would remain behind until the last casualties could be evacuated. This became a normal procedure. In Europe, the airborne battalion aid station had been pared to less than ten men to avoid just such a situation. Size was sacrificed for celerity. But this was only possible when evacuation was constant. That condition did not exist on Iwo Jima.

Throughout the book, I was struck at how irregularly Vedder’s aid station was cleared. They found more modes than stars, co-opting anything with tread or tracks. A particularly desperate scene occurred on D+7 when they flagged a graves registration truck. Wounded men mounted a stack of dead ones because the demand of Vedder’s lone jeep was stretched by an advance — of two miles. That made a four mile round trip to the hospital and back. If the driver was really expeditious, he could carry 10 wounded an hour. Leveraging beaucoup jeeps and the regimental aid station — conspicuously absent in Vedder’s book — was the secret ingredient of the European airborne battalion. They were speedy at evacuation. But that doesn’t mean it was easy. They often experienced just as much friction as Vedder on Iwo Jima.

Certainly there’s little alike fighting on a continent from an ocean island. But if anything is proven by the contrast between continental Europe and Oceanic Iwo it’s that casualty evacuation is one of those ethereal traits battle brings. And that evacuation’s immutable characteristic is — it’s just plain hard.

By any measure, this singular topic is of pinprick scope. However, it hints at something broader, something more fundamental about battle: its essence is unchanging. There are certain tasks that have to occur when you put soldiers in the mud, like casualty evacuation. No matter the (new) technology, no matter the (new) strategy, no matter the (new) ideas. It may not be done as before, and as this contrast illustrates, it may not even be done the same way in the same year, but the problem that presents is enduring. Impervious to progress is battle’s essence, and all the mystical forces that descend with it.

So far had the art of communication advanced, so powerful were the transmitters, so swift the coding… that the far-off high commands could watch this entire battle like Homeric gods hovering overhead, or like Napoleon on a hill at Austerlitz. The Battle of Leyte Gulf was not only the biggest sea fight of all time, it was unique in having distant spectators. …

It is interesting, therefore, that nobody on the scene, or anywhere else in the world, really knew what the hell was going on. There never was a denser fog of war. All the sophisticated communication only spread and thickened it.

— Herman Wouk, War and Remembrance

Ridgway’s Notebook X The Company Leader

The first of this week, my friends at the The Company Leader posted one of my essays entitled, “LSCO Ready: Organizing and Equipping for Airborne Medical Care in World War II.” Titling this piece was a challenge for me. Its working title was “A Soldier’s Guide to Battle Surgeons.” Pretty bad. But it was the clearest reflection of the original intent: I wanted to make a reference guide for practitioners on prescient themes. Yet as B.A. Friedman says, “No writing plan survives first contact with the pen.”

The essay which appeared at The Company Leader is divvied up into five themes. Page numbers corresponding with the book did not accompany the published essay, but I felt it beneficial for interested Ridgway’s Notebook readers to post them here.

MOTORIZATION (P. 19-21 & P. 110-112)

ORGANIZED FOR PURPOSE (P. 109-113)

TASK ORGANIZATION (P. 128-135)

SUPPLY (P. 130)

SO, DID IT WORK? (P. 157-158)

BEAT NAVY!

Of course, history is more complex and nuanced than this, but bear with me for the effort of contrast.