Welcome to “Ulysses of the Parachute Infantry,” a series where we get to know Sergeant Ross Carter, the regiment to which he belonged, and probe the tales behind his magnum opus, Those Devils in Baggy Pants.

“Things like that are always being left out,” Francis Keefe would tell me of the lemonade packets they would toss with discontent. In the winter months, they were unwelcome to these swashbuckling warriors. I was a young man when he said these words to me. Francis was securely in his 90s.

That time in my life, I found my interests arrested by men like Francis Keefe. As veterans of the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment, they had seen battle in many of World War II’s headlining campaigns. With a tense, restless anticipation I would monitor my phone and inbox to hear first-hand their accounts of the Homeric epics they lived. The details were gripping and illuminating. They were of an intimate perspective, illustrating the things that make one taste, smell, and hear the goings-on of a company of infantry: the banter; the jostling between the Protestants and Catholics of a platoon (where how many were wounded of each kind determined which side God was on); the fatalism; the complaints of the rain and the cold—and because they drew a ration with lemonade powder.

There was an essence about these stories that was intangible, unrecordable.

It was unrecordable by someone who never lived it, at least. The essence was emotion coming from the teller. Emotions of intimate connections to the story, to the comrades, and to subtle details which could make the receivers gut turn to knots as if their own best friend were under shellfire.

Now these men whose stories and ideals helped father me in my most formative years are gone. That essence is buried with them.

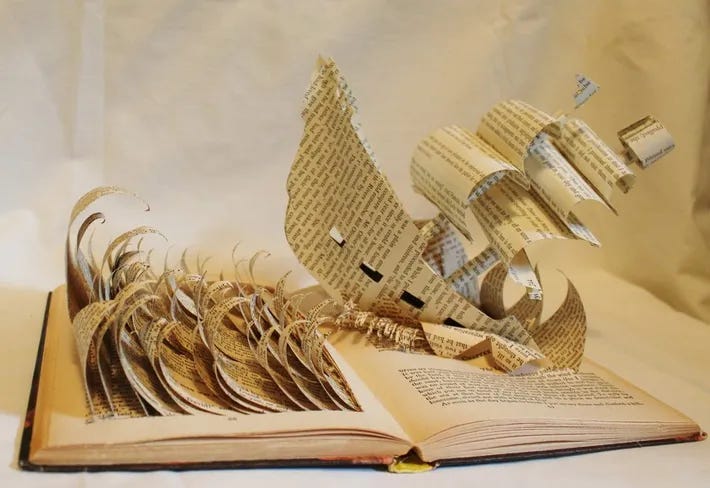

Except when I open the pages of one particular book.

Blessed with the gift of prose and human emotion, one of their number lived just long enough to etch this essence in literature. “He was pale… He really fit the picture of an old wore out combat man,” a squadmate recounted. The man was Ross Carter. He was gentle-talking, always with a book — Homer was his favorite — and in the closing days of the war, with a crooked stick pipe. “He was well respected. I didn’t ever hear anyone downing Ross Carter.”1

Ross always did mention that someday he would write a book about the outfit. It’s really too bad that he didn’t live to see it published cause writing the story was always on his mind and he discussed it quite often. Actually I think it would be just as easy for someone to write a novel about the 504 and center it around Ross Carter! There are many stories about Ross, his heroic deeds, bravery under fire, and numerous other incidents that would put any ordinary hero to shame! I’ve spent a lot of time with men, mostly in combat, and always said repeatedly that Ross was without a doubt the coolest and one of the bravest I’ve ever seen. To me, [he] represented THE All-American soldier — level headed, cool at all times, and seemingly with nerves of steel. This is just not my opinion, but that of any of the men who ever fought alongside of him.2

Between the summer of 1945 and mid-autumn of that year, Ross Carter drafted his manuscript in a Virginia home, nestled within the folds of the Appalachians Ridge-and-Valley range. Frank Dietrich, who would appear as “Berkley” in the developing epic, slept while Carter forged the tales of their war adventures into Those Devils in Baggy Pants. Carter’s and Dietrich’s relationship is one of the stoutest of the book. They shared that corse brotherly love, forged in hardship and expressed by banter. It was a relationship which could only have its foundations in battle.

They moved us to Laon, France for a few days to regroup and that’s the first time I met Ross Carter, and we were staying in an old French fort, it must have been there before the First World War... Even the concrete steps were worn down real noticeably. We had double deck bunks we just made out of lumber. I was [laying down] on the top bunk and Carter was the O.D. – officer of the day – and his office was right around the corner and he was passing out mail or something… Carter came out and he was carrying on a bit. Back in those days they have newspapers and boys would be peddling them... He had this order giving Dietrich his second Silver Star so he was reading it out like a newspaper back home and he was saying, “Read all about it! Frank Dietrich gets another Silver Star!”… He snatched that out of his hand.3

Those Devils in Baggy Pants is fundamentally about relationships: a man’s relationship to a battle, and the relationship amongst squadmates, such as that which passed between Ross Carter and “Berkley” Dietrich. The former Carter most explicitly addresses in Chapter 19 and in the opening soliloquy of Chapter 26. The latter is the book’s soul, an authentic illustration of the interplay within a World War II rifle squad. It’s an illustration Army historian SLA Marshall would have appreciated. Some of Marshall’s ideas of men and their interaction with their squad, laid out in his controversial Men Against Fire, are brought to life within the pages of Those Devils in Baggy Pants. In battle, we see the squad stiffened by the bull-like personalities of “Berkley” Dietrich and T.L. Rogers. Those strong personalities, Marshall says, provide leadership in absence of rank. They serve as (as Carter once described Rogers) a “pillar” for their comrades.4

But although these large personalities provide natural leadership for those around, historian Marshall argues that they don’t pull combat out of men. Giving combat, he says, is not inspired from above (by officers) but laterally across the small squad. Among the drivers of giving combat, or so Marshall argues, is not to be thought of as a coward by squadmates. Carter, for instance, sometimes alludes to wanting to give a good account of himself in battle (he did). It’s also the subject of his sole surviving poem (come back next week to read it).

Before the door had closed on the year 1945, Those Devils in Baggy Pants was completed in rough draft form and Carter and Dietrich were in the Army again. Ross Carter would not see his literary passion come to pass. Scarcely two years later, he discussed and then entrusted desired edits of the manuscript to his brother Dr. Boyd Carter, a professor of literature, from a hospital bed in Walter Reed. A few weeks later, Ross Carter went to join the comrades he once saw marching by in a vapor-filled vision. They were “phantoms,” marching to the aether, beckoning him to follow.5 And on April 18, 1947, he would.

Through his gift of prose, Carter left alive a world where the Master Termite still fantasizes of his future home above Hoboken Bay; where the epics of Homer still whorl around the foxhole of the thorough-going Arab; where the squad marches around another bend as Duquesne grins ear-to-ear, mocking Gruening for his drooping sack of iron rifle grenades; and T.L. Rogers’ socks, that wrenching talisman, still protects.

Between two pieces of cardboard bound by fibers these men reside. When I open them, it’s as if Francis Keefe is there again, telling me about his lemonade packet.

“Finkelstein alone was undaunted.” Etched in cold stone north of Boston is name of Raymond D. Levy. He lives in Those Devils in Baggy Pants, under the Nom de guerre of “Little Finkelstein.” Of all of Carter’s immortal characters, Little Finkelstein is perhaps the most endearing. Squat in statue, but stout of heart, Little Finkelstein feared no man. If you are in the Boston area, it’s a worthwhile thing to pay your respects.

📚READ OF THE WEEK📚

Join us next Saturday on Ridgway’s Notebook for:

“The Ulysses of the Parachute Infantry: The Man Who is the Regiment”

Dodd, Gilbert E. Interview with Tyler Fox, January 24, 2014

“Duffield Paratrooper Writes Bestseller.” The Post, September 27, 1951. This letter was likely written by Frank Dietrich.

Dodd, interview. Sgt. Ross Carter was wounded on 20 December 1944 in Cheneux, Belgium. He did not return from the hospital until February 24, 1945 while the regiment was resting in Lyon, France. Gilbert Dodd had joined the squad led by Sergeant Carter in the interim period. In a letter two days after arriving from the hospital, Carter described the feeling of joining a squad full of “Dodd’s” - clean-shaven strangers. It is quoted in the Epilogue of Those Devils in Baggy Pants.

The controversial part of Marshall’s book is his claim that only 25% of men actually fired their weapon in combat. This part is not borne out in Carter’s book, and many senior airborne officers (including James Gavin) took issue with this assertion. I recommend the University of Oklahoma Press edition published in 2000 for its introduction providing a good overview of the arguments of Marshall’s dissenters. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Men_Against_Fire/rsfA3LkUsTYC?hl=en&gbpv=1

This vision is described in Chapter 44.

Great read, I can’t wait for next week!

Another great read. Can you share the location of the Levy grave for the folks who wish to pay respects?