Under Canopy

History's Duplicity

Welcome to Ridgway’s Notebook, your home for airborne PME. We offer penetrating essays on military history. Through the World War II experiences of General Matthew Ridgway and the 82nd Airborne Division, we illustrate some of the similarities between the questions asked by officers of the 82nd yesterday and today—and dissect how they came to be.

I have railed relentlessly against the airborne medical company’s structure. I’ve employed adjectives like, “unsound,” and built them into phrases like, “not built for purpose.” And this is true — for the cinematic battles which unfolded on the European plains. But history’s lessons are nuanced. My conclusions about the medical company would be themselves unsound if applied elsewhere, even within the same war. For, concurrent to their failings on one side of the globe, their successes were cast in full light on another.

The trails belabored even the stoutest heart. Living on Leyte was hard, and not even because of any enemy. The trails threaded precipitously across mountain backs impervious to anything that cushioned life. It was hard to tell if it was the jungle or the mountains that made things so, or if it was the marriage of them. Even so, men of the 11th Airborne Division saddled hardship and melded into the mountainous jungle. They would prove what had been disproved in Holland — the soundness of the airborne medical company.

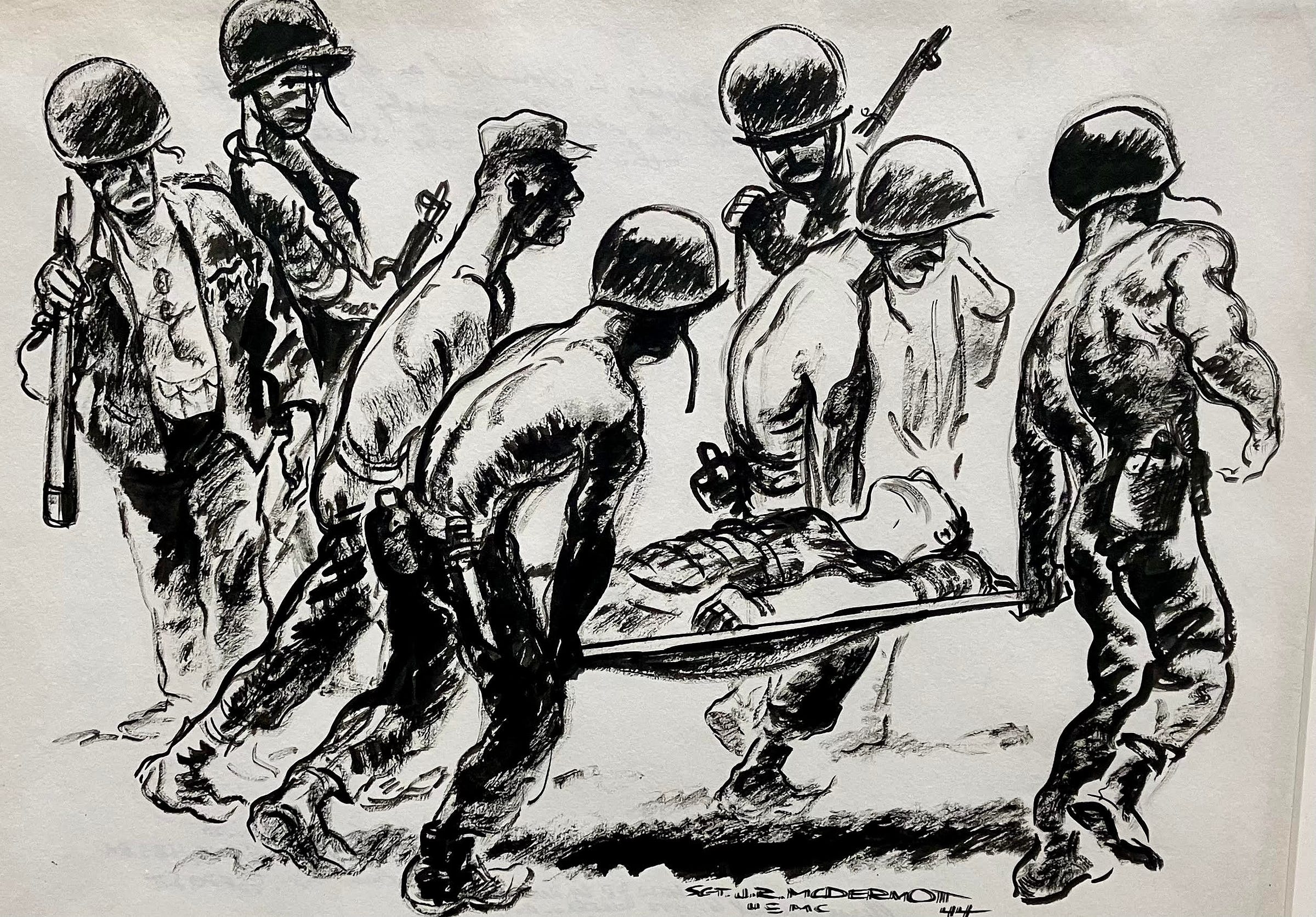

The jungle war was queer. Terrain simultaneously dense and vertical imposed isolation. Battalion- and company-sized units established themselves and the 11th began a “war of posts.” They were threaded loosely and unreliably by trails which churned to mud under crushing rain. Porters struggled for purchase. To be wounded was to become an unfathomable burden. Eight to twelve men, plus security, were required to carry one casualty for two days.1 Industrious as their commander was, a solution was not long.

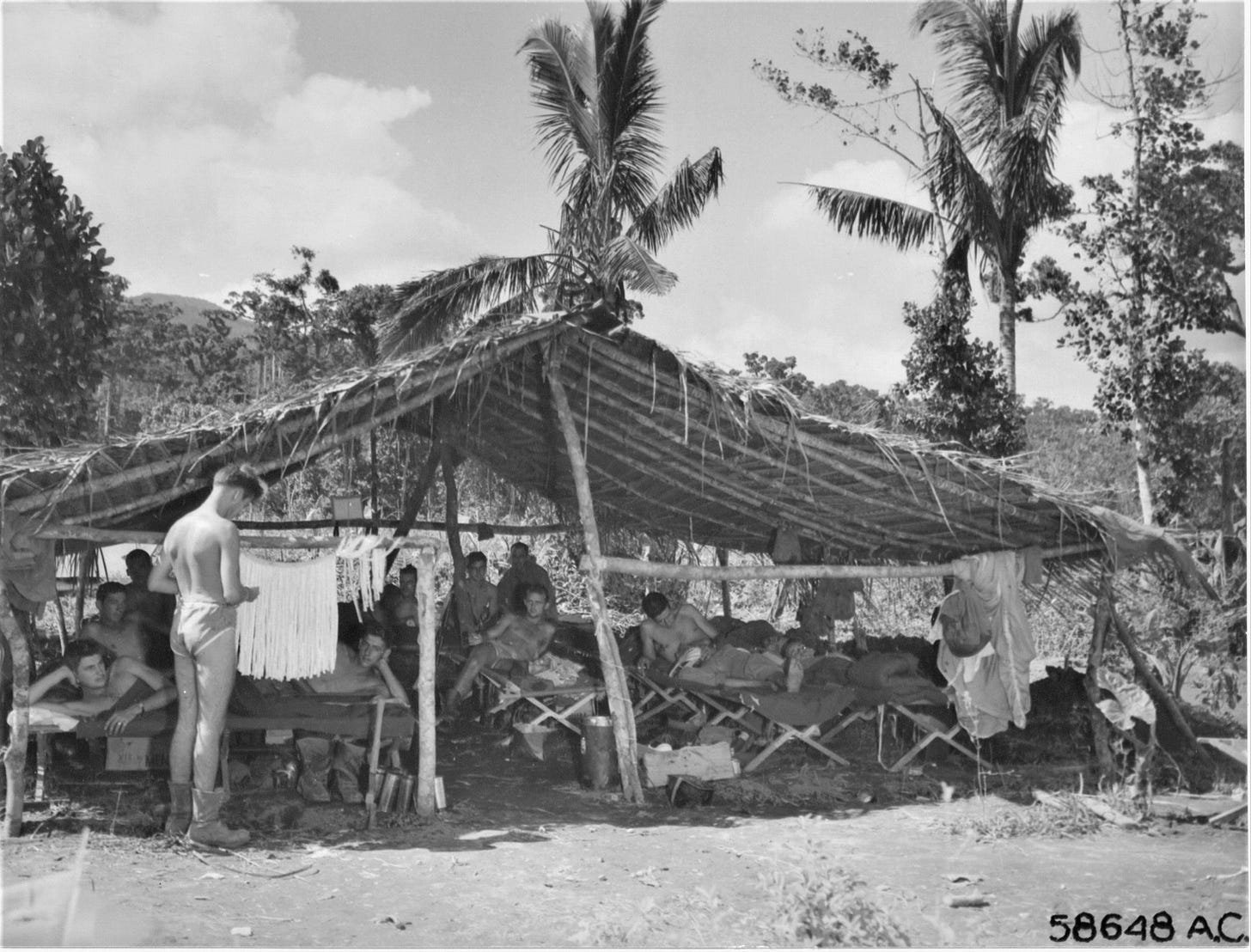

Little L-5 and L-4 grasshoppers — Piper Cubs — were marshaled into a fleet which could drop supplies on the posts and patrols. The medical service enlisted them, too. From these dainty little planes a platoon of the 221st Airborne Medical Company parachuted into the jungle at Manawarat, one man at a time. As a small airstrip for the grasshoppers was bushwhacked, bamboo was felled and thatched into a shelter. The small hospital was crude, untidy, and native. But here they could serve in a capacity suited to their design, a small, independent instrument of care. Here, they preformed miracles.

The three surgeons and 10 aidmen preformed operations for belly wounds (2), head wounds (3), and chest wounds (4) in a dugout. There were eighteen compound fracture cases. Supplies were parachuted in from the grasshoppers.2 General Swing was proud of their work. “The men are receiving the same care they would receive in a field hospital,” he boasted. Ice cream was even air-dropped. (The division had purchased a machine in Australia and convinced a C-47 crew to fly it to the beachhead).3

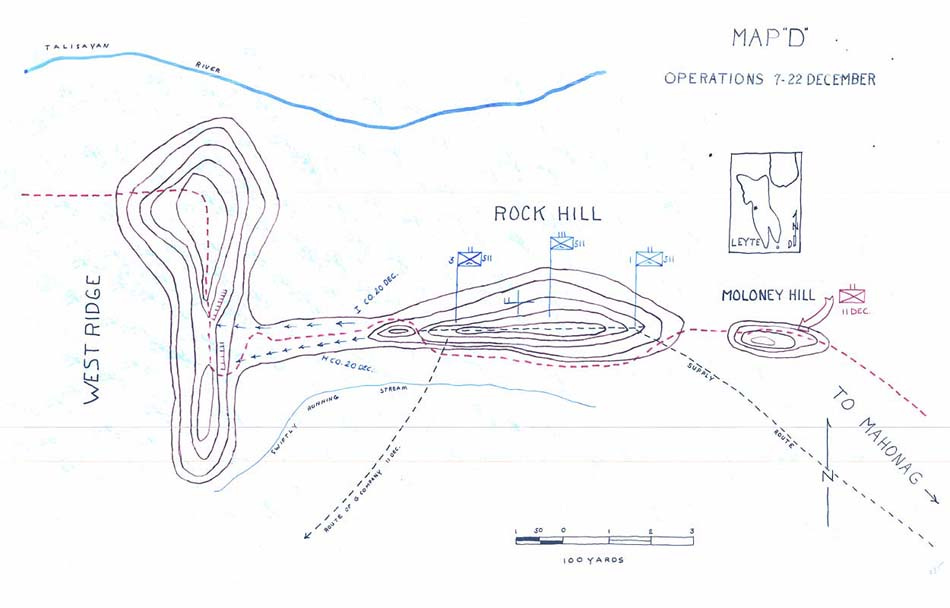

As the 11th encroached their posts westward, they parachuted in another medical platoon at Manawarat. They were to march the trail to Mahonag, where they would marry with the medical supplies dropped to establish another small hospital.4 A platoon leader in the 511th PIR wrote, “Mahonag was a stump-studded clearing on top of a commanding hill, about 400 by 500 yards, that had been used by the natives and Japs as a cammote (sweet potato) field. It was covered by prepared positions and showed evidence of a Jap bivouac; but they had withdrawn to the surrounding jungles and hills.”5 Between these two medical platoons, pressure to clear casualties all the way to the rear was greatly reduced. This preserved fighting strength; it allowed them to convalesce men who would otherwise have to be evacuated. They were able to return many to duty. It was suited to this “war of posts” because all the requisite pieces to provide care were deliverable at multiple points, by platoons.

The war of posts was played like a chess game. The Japanese played to make the squares untenable by cutting the supply trails. General Swing denied them.

One of the queer things about the jungle fighting was the Japanese supply trail and the 11th’s supply trail ran parallel to each other, and were closest at Mahonag. Paratroopers straddled this trail at Rock Hill and forced the Japanese to fight for it. “I get a kick out of beating the Japs at their own game,” General Swing wrote conspiratorially.

Swing employed tactics like infiltration and ambush. It was not a battle of regiments arrayed on broad country which produced wounded with industry — the primitive hospital at Manawarat only saw 116 casualties. This dwarfed the numbers in Europe. In a comparable timeframe, the 307th Airborne Medical Company saw 700 casualties. They dealt in wholesale, and they did it by consolidating into one large treatment center: they did it by shucking platoons. Interior lines were robust in Europe.

For every solution a commander constructs from his problem, the historian yields a lesson. He is apt to give it new life, codify it, pluck it from its purpose, make it fact. But lessons must be jealously guarded, meticulously probed, and precisely applied. Applying the September 1944 lessons of Holland to a Pacific island in December 1944 would have resulted in a lot of dead troopers.

Interested in learning more about General Joe Swing? Check out this previous edition of Ridgway’s Notebook!

📚READ OF THE WEEK📚

“Report After Action with the Enemy, Operation KING II, Leyte Campaign.” Headquarters, 11th Airborne Division, 28 May 1945.

Surgery in World War II: Activities of Surgical Consultants. Volume 1. Office of the Surgeon General, United States Army. p. 502

Major General Joseph M. Swing to General Payton March. Letter, 15 December 1944.

“Report After Action with the Enemy.”

Richard V. Barnum “Operations of the 3rd Battalion, 511th Parachute Infantry…”

Outstanding! Love reading about the bad assery of the 11th! I read a story about them defending against a Japanese airborne assault. I think it’s the only time American airborne troops did that. I know we fought German airborne troops but they never jumped on us to my knowledge.

Hmm, chess? I wonder how it might look on a Go board.